―3― ―3―

ANNALS OF EUROPE AND AMERICA.

CHAP. I.

POLITICAL transactions are connected together in so long and

various a chain, that a relater of contemporary events is frequently

obliged to carry his narration somewhat backward, in order to make

himself intelligible. He generally finds himself placed in the midst

of things, and quickly perceives that he cannot go forward with a firm

and easy step, without previously returning to some commencing

point. An active imagination is apt to carry us very far backward on

these occasions; for, in truth, the chain of successive and dependent

causes is endless; and he may be said to be imperfectly acquainted

with the last link, who has not attentively scrutinized the very first in

the series, however remote it may be.

An American observer, who proposes to give an account of pas-

sing events, immediately perceives that the field before him naturally

divides itself into foreign and domestic. It may seem, at first sight,

that his concern is only with the latter; but a little reflection convinces

him, that the destiny of his own country is intimately connected with

the situation and transactions of European nations. As trade is the

principal employment of the American people; as their trade is chief-

ly with the nations of Europe, or their colonies; and as the present

state of navigation renders the whole globe a theatre of commerce to

more than one people, our situztion is deeply influenced through the

medium of traffic, by the domestic condition and mutual operations

of European states. If they are at war among themselves, those

wants which, in peaceable times, were supplied by one another, must

now find a supply elsewhere, and whatever influences their manufac-

tures and produce on one hand, and their consumption, or the chan-

nel which feeds it, on the other, is deeply interesting to a country

like our own, which has both the inclination and the power to extend

and dilate its commercial dealings almost without limit. Trade and

navigation likewise have the wonderful power of annihilating, in its

usual and natural effects, even space itself. They bring into contact

nations separated by half the diameter of the globe, and supply them

―4― ―4―

with occasions and incentives for rivalship, jealousy, and war. Two

maritime and trading nations encounter and interfere with each other

in every corner of the globe that is accessible by water. With France,

Spain, and England, America has not only the relations incident to

trading nations, but, by means of their colonies, she is, in some re-

spects, directly or indirectly the territorial neighbour of all of them;

and with all of them, therefore, she is liable to those disputes which

flow from clashing interest and irritated passions, both on land and

water. Hence the interest which we may reasonably take in the wars

and negociations of European states among themselves, since their

conduct towards ourselves, their inclination and power to benefit or

injure us, so greatly depends upon their situation with respect to each

other.

The two leading nations in the world, and especially in Europe, are

undoubtedly France and Great Britain. For more than half a century,

these states have exercised absolute sway upon the movements and

councils of the rest of Europe. War and peace have appeared and

disappeared, for the most part, at their bidding. Other nations have en-

tered the lists at their instigation, and have carried on war by means

of their assistance, either in money or soldiers. If war has not, in

all cases, originated in the intrigues and bribes of these two states, they

have always thought it necessary to intermeddle with the combatants,

and to exasperate, extend, prolong, or terminate the warfare, accord-

ing to the impulse of their own interest. This interest has generally

a relation to each other, and they have fomented or suppressed hostili-

ties beyond their own respective limits, chiefly with a view of annoy-

ing each other. The history of France and of England, therefore, is

the history of Europe, and, in some measure, of the world. It forms,

especially, an important branch of the history of our native country,

because those are rich, maritime, and trading states like ourselves,

and beset us on all sides, either by their ships or their colonies.

At the present moment, France and Great Britain are at war with

each other. France has sufficient influence with Spain to engage her

in the same contest. The same may be said of Holland, if Holland

may, without impropriety, be considered as a separate state. Turkey

has been lately rendered, by one of these accidents, which are impos-

sible to be foreseen or prevented, subject to the influence of France,

and is at war with England. An equality of influence maintains Aus-

tria and Portugal in a state of neutrality. War at present rages be-

tween Russia and Prussia on one side, and France on the other. With

regard to Russia, this war may be said to have been instigated by

Great Britain, but in relation to Prussia, the present contest affords a

striking exception to an observation we have just made, as to the joint

influence of France and Great Britain on all the affairs of Europe.

Prussia appears to have gone to war with France, not only without the

instigation of the English, but at the time when she was at enmity,

and almost at open war, with that state. At present, indeed, she is

aided in carrying it on, in some degree, by the countenance and

money of the latter nation; but it commenced with so much precipi-

tation as to preclude the co-operation of all foreign powers.

―5― ―5―

The present war between France and England may be said to have

originated fourteen years ago. As it has been of longer dura-

tion, and accompanied with more memorable events, than most former

wars, it is likewise singular and unexampled in its origin. Formerly,

these nations quarrelled about territory, at first within the limits of

France, and afterwards, when the English were entirely expelled from

the French limits, about territory in Asia or America. The most

common source of contention, in later ages, was the jealousy entertain-

ed by England of the aggrandizement of France, even though that

aggrandizement were purchased at the expence of other nations.

The obvious policy which leads us to secure ourselves from future

danger, by preventing an increase of power in one whose situation and

temper are best calculated for annoying us, induced the English to go

to war to prevent France from acquiring new provinces in Italy, Flan-

ders, or Germany. Hence chiefly arose the war concerning what

was termed the Spanish succession, at the beginning of the eighteenth

century. The king of Spain left his dominions, by will, to a grandson

of the French king, and his subjects were sufficiently disposed to ac-

quiesce in this arrangement, but the intimate alliance and constant

co-operation that was likewise to follow the fulfillment of this will be-

tween France and Spain, formed a powerful motive for England to

forbid it, and to aid the pretentions of Austria to the Spanish throne.

The same motives impelled England to go war, in defence of Austria,

and afterwards to take part in defence of Prussia, against France. As

our neighbours are disabled from injuring us by intestine war and

faction, it has always been the policy of states to disseminate and

foment political dissentions among their neighbours. The expulsion

of the Stuart family in 1688, gave rise to a long series of factions

and commotions in England, which France failed not to promote and

foster. The quarrel, likewise, between Great Britain and her colonies,

in 1776, presented a favourable opportunity to France for reducing

the formidable power of her rival, by aiding her revolted subjects.

From the humiliation or subjection of the Calvinists of France, and

the extinction of an unruly aristocracy in the minority of Louis XIV,

till the opening of the revloution in 1788, the internal state of France

exhibited a scene of uninterrupted order and submission, and depriv-

ed the neighbouring states of that advantage, which they are sure

to make the most of, when a rival nation is afflicted with anarchy and

intestine war.

There were no inveterate factions and divisions, which England, or

Spain, or Austria might employ to weaken the external efforts of

France, either to protect itself, or impede their aggrandizement.

That year, however, opened a new scene. The earliest changes in

the French government were in the highest degree benign and auspi-

cious. They seemed to have a tendency, not only to advance the in-

ternal felicity of the nation, but its power and opulence. In this re-

spect, they would naturally excite the apprehension of their neigh-

bours; but with regard to the English, their vanity was flattered by the

notion, that France was only copying the model of their own constitu-

tion, and affording a new and practical testimony of its excellence.

―6― ―6―

They regarded the French in the unoffending light of pupils and ad-

mirers, and exulted in innovations and improvements which they con-

sidered as flowing from their own precepts and example.

This illusion was speedily at an end. The French hastened preci-

pitately to a point, as much disliked and detested, by the ruling par-

ty in Great Britain, as that from which she had set out. Good-will

and complacency were converted into hatred and suspicion. The

madness of the French enthusiasts, who openly avowed their design,

or, at least, their wishes, to introduce their own political system into

other states, inspired all their neighbours with implacable hostility,

and a general war was the consequence.

The real motives and movers of the war between France and Eng-

land have been a subject of much controversy. There are supposed, by

politicians, to exist among mankind, a set of people who apply to the con-

duct of nations a certain scale of abstract justice and reason, and con-

demn or applaud that conduct accordingly. To this* imaginary tribu-

nal, statesmen think it necessary or convenient to appeal when they go

to war, and to prove, by a grave detail of facts, that their enemies have

been aggressors. Notwithstanding all the appeals made on the present

occasion, it is still a matter of doubt whether England commenced hos-

tility, or the first provocation came from France. By some it has

been thought, that the ruling faction in France considered a war with

England as necessary to the overthrow of their opponents By others

it has been said, that the British ministry believed that the prevalence

of what were called French principles could only be checked and di-

verted by war, and that it was necessary for the preservation of the

constitution from change, if not for protecting the territory from con-

quest.

The leading events of this war are well known. The allied of Eng-

land, Spain, Austria, Sardinia, the Pope, Naples, Holland, and Rus-

sia, have been defeated, repulsed, disarmed, or subdued by France.

Several confederacies have been dissolved by the disunion of the par-

ties, or by the victories of the French. The English, on their own

element, the sea, and with their proper weapons, those of a naval

war, have been crowned with uniform success. Their power in Asia

has ascended to a higher pitch than ever. In consequence of their

naval superiority, they wrested from the French two of their most

valuable conquests, Egypt and Malta. They have destroyed the navy

and commerce of France, and baffled every effort of their enemy to

invade their territory. In this state of things the two nations agreed,

in 1802, to a peace so short and precarious, that it can scarcely be

considered as a suspension of war. On that occasion, the English

agreed to restore Martinico, Surinam, the Cape of Good Hope,

Porto Farraio, and Minorca. They acknowledged the new Batavian

republic, and the republic of the Seven Islands, both formed and up-

* It cannot be denied that, in the nature of things, there is such a standard;

but it is unquestionable that it has no influence whatever on the conduct of

states; that the facts to which it is applied are almost always involved in in-

curable uncertainty, and that judges, so far void of prejudice and passion as

duly to apply this test, are no where to be found.

―7― ―7―

held by the influence of the French. The French, on their part, con-

sented that the English should retain the island of Trinidad, conquered

from Spain, and Ceylon, taken from the Dutch. They agreed to

withdraw their troops from Naples and the papal territory, and to pro-

cure a territory in Germany for the house of Nassau, equivalent to the

estates and authority which it lost by the establishment of the Batavian

republic. On all these points their agreement appears to have been

easy. The only difficulty which occurred related to the future destiny

of Malta.

This island, which, before it was transfered by the emperor Charles

V to the order of St. John, was a naked rock, occupied by fishermen,

has become, under that celebrated order, an impregnable fortress, and

a safe and commodious harbour. In the safety of its port, and the

convenience of its position for trade and naval operations in the Me-

diterranean, it is far superior to Gibralter. It is, artificially, quite as

strong, and from situation much more difficult to assail or to conquer.

The same motives, therefore, which endear Gibralter to the English,

may be expected to operate with still more force in favour of Malta.

Both places, however*, are, in effect, merely sources of vast expence,

and the latter is of less consequence to England, from any direct be-

nefit flowing from possessing it herself, than from the injury to which

her trade would be liable in time of war, if it were in the hands of an

enemy. There was therefore no reluctance to relinquish it, provided

the new holders were disconnected with France, and could be secured

in the possession. This was evidently difficult, if not impossible; and

the complex regulations made for this purpose, in the treaty of Ami-

ens, were doubtless nugatory, as long as the order was composed of

catholics, and consequently drawn from countries under the influence

of France. The treaty meanwhile was ratified, because the surrender

of Malta depended on future contingencies.

It is well known that the refusal of the English to surrender Malta,

in consequence of new encroachments made by France on the inde-

pendence of her neighbours, occasioned a renewal of the war. The

same causes, likewise, excited a new war between France and Austria,

which ended, in a single campaign, by the conquest of the greater part

of the German territories of the latter. They were redeemed by a

treaty, in which the pre-eminence of France in Holland, Switzerland,

and Italy was established, and a transfer made to her of these territo-

ries, which anciently belonged to the republic of Venice.

* The works at Malta require a garrison of seven thousand effective men,

but that naval superiority which can only supply Gibralter when besieged, can

altogether prevent the siege of Malta. Two-thirds of the annual consumption

in grain are imported from Sicily. It is itself no source of commerce, and the

British Levant trade was so low, that it was not worth while to retain Malta

for its security.

―8― ―8―

CHAP. II.

THE cessation of hostilities in every other quarter, allowed the

French, in the early part of the year 1806, once more to direct all their

efforts against Great Britain. As that island was wholly inaccessible

except by water, as its colonies and commerce were secured from all

attacks by its naval superiority, there remained only a project of di-

rect invasion, in which there was any possibility of success. This pro-

ject was recommended by the imagined superiority of the French

troops in numbers and discipline to those of England, a superiority

arising from the military habits and experience of the French nation,

and the long internal tranquility and pacific institutions of the Eng-

lish, and by the proximity of their opposite shores, in consequence of

which, it was thought possible to effect the disembarkation of a great

army in England, without the necessity of a regular battle at sea.

France and England are separated by a channel, which widens some-

what gradually, from an interval of twenty-two miles, to one of four

times that breadth. At the narrowest part, therefore, the passage can

be effected in a few hours, and at the widest, it would be possible to

effect it in a single day. That station on the French coast, which

unites the advantages of being nearest to England, and of affording

security to the shipping necessary to invasion, would, of course, be

fixed upon by the French as the centre and commencing point of all

their preparations. Boulogne, about forty miles south-east of the

nearest part of the English shore, is so far suitable to this purpose,

that its shallow waters prevent the access of very large ships, and an

extensive line of fortifications can keep a hostile fleet at a harmless

distance. To Boulogne, therefore, the war between France and Eng-

land may be said to have been, for some years, almost entirely con-

fined: one side employing all its ingenuity and power in mustering

armies and preparing shipping at this point, and protecting them

from injury; while the other had been equally vigilant and active in

watching and disturbing the progress of these preparations. One

party was continually in search of new expedients for facilitating, and

the other for preventing, the passage of the channel. Hitherto, the

French had not completed their preparations, or had not found the op-

portune moment for beginning their voyage; while the English, with

all their industry, had not been able to make any sensible impression

on the armament in its actual state. The possibility of effecting this

invasion, if not in open opposition to a hostile fleet, yet in conse-

quence of a certain state of wind and weather, by which one would be

enabled to move forward, and the other be hindered from advancing,

impressed the English government with a great and salutary terror.

They saw the necessity of providing a great military force to oppose

the invading army on its landing, and it has long been anxiously en-

gaged in deliberating on the best mode of forming and distributing this

military force.

―9― ―9―

There would, at first sight, appear to be little difficulty on this

head. The same institutions which have rendered the French so

formidable, would have the same influence on another nation. The

difference, as to mere number, between the population of France and

England, is wholly immaterial, in cases where the latter exerts itself

in defensive operations. In constitutional strength and courage, the

two nations cannot be supposed to differ. In those moral elements

which constitute a soldier, attachment to the cause in which he is en-

gaged, and obedience to discipline, it would be equally absurd to sup-

pose any disparity between them. The modes adopted by the French

for selecting, arming, and disciplining a certain class or proportion of

the people, and preparing them for service when wanted, are equally

practicable in both cases. There are indeed diversities in the situation

of the two nations favourable to the French. In the first place, the in-

vaders would necessarily be superior to their opponents, both soldiers

and commanders, in those qualities which are produced by actual ex-

perience in war. This disadvantage on the English side, whatever

be its magnitude, cannot be removed, the must therefore be endured.

So far as it can be outweighed by superior numbers, it would be easy

to obviate it, because in England the persons qualified for military ser-

vice, compared with the greatest number which the French could

bring to the attack, would be as ten or fifteen to one. In the second

place, the French, with a veteran army, would commence the attack

suddenly, and at one point. The British metropolis is within forty

miles, or one day's rapid march, of the nearest shore, and of that shore

which is most commodious for landing an army from France. It

would be difficult, therefore, if not impossible, to collect a sufficient

force, on so short a warning, to make head against them. This ad-

vantage, if incurable, must likewise be submitted to in patience, and

without discussion. If it can be lessened or removed by multiplying

fortresses on this side, or by establishing as large encampments of

troops, near the south coast of England, as the French shall form on

theirs, the remedy is obvious. Notwithstanding this state of things,

however, the proper mode of resisting an invasion has given rise to

endless consultations and debates in England. Several modes have

been successively adopted and relinquished. Different opinions are

maintained with regard to the usefulness, first, of increasing the num-

ber of inland fortresses and strong holds; next, of relying on the aid

of large bodies of volunteers; thirdly, of different modes of enrolling,

equipping, and disciplining the inhabitants who are of a military age

and constitution; and, fourthly, of augmenting, decreasing, or distri-

buting the regular army. As no system can be carried into effect

without the sanction of a legislature, consisting of two numerous bo-

dies, whose deliberations are public, and as the press is open to the

political lucubrations of private persons, it is surprising and amusing to

survey the innumerable schemes and arguments which this interesting

topic has produced. In this place, we can only make this general al-

lusion to them, and observe, that, in the summer of 1806, a military

force, including regular and militia troops, was maintained, by Great

Britain and Ireland, at the enormous expence, in the whole, of more

―10― ―10―

than twenty millions sterling, or nearly ninety millions of dollars, a

year. This force was indeed distributed throughout the world, in Af-

rica, in Asia, in the Mediterranean sea, and in America, but, of course,

the greatest part was stationed at home, and in such a manner as to

afford prompt assistance against any domestic enemy. Though the

best made of defence against a French invasion was still the subject

of ardent controversy within and without the senate, it must not be sup-

posed that that defence was wholly neglected: on the contrary, an ex-

tensive scheme of conduct for encountering every exigence that might

ensue was adopted, fortifications were raised along the coast, and

troops distributed in places where opposition to a foreign army might

be most effectually made.

In discussing the best mode of defending their country, the British

nation are compelled to pay attention to two circumstances: the ex-

pence and the demands of agricultural and manufacturing labour.

The spirit and habits of the people are such, that a million of well dis-

ciplined soldiers might be encamped, for an indefinite time, on the

coasts of Kent and Sussex; but if the present force requires twenty

millions sterling a year to support it, a larger, and of course a more

expensive, preparation would be impossible. As the increase of the

army would augment the expence, it would likewise, in the same pro-

portion, lessen the income of the public, by depriving the various arts

of their customary workmen. The great point in view, therefore, is

to qualify and oblige the young men of the nation to take up arms,

and march only when their services are wanted, but previously to al-

low them to pursue their several occupations without interruption.

As the domestic security of England is promoted by raising enemies,

and thus affording employment to France in other quarters, the British

government has always been industrious in sowing dissention between

France and her neighbours. To impute to her influence all the wars

that have taken place in middle and western Europe of late years,

would, however, be extremely absurd. The maxims of the French

revolutionists, with their conduct in destroying the royal family and

abjuring religion and monarchy, were amply sufficient to excite a spirit

of hostility in all surrounding nations. Their successes in the wars

they have carried on have merely brought about a compulsory peace,

and left, in the states they have conquered, a sense of injury and in-

justice, which only waits an opportunity of showing itself. In addi-

tion to all those motives of jealousy and ambition, which have actuated

the French and Austrian governments against each other for some

centuries, the former has, during the last thirteen or fourteen years,

heaped upon the latter every imaginable species of insult and injury,

and nothing but an utter despair of success, on the side of Austria,

can ever induce that government to submit to its present humiliating

destiny. The pecuniary aid of England, though never a principal,

was no doubt an auxiliary motive for Austria to quarrel with France,

and this kind of assistance has always been liberally granted by the

British to the enemies of their great and sole rival. The war which

terminated with the battle of Austerlitz reduced the Austrian power

so low, that even Britain herself was forced to acknowledge that a new

―11― ―11―

war between France and Austria was rather to be deprecated than de-

sired. The diversion in her favour, produced by such a war, could

only be expected to be momentary, while the issue of the contest

would inevitably raise the power of France to a still more formidable

height. The same considerations had still more weight in the British

councils, with regard to Portugal. They were satisfied if Portugal were

unmolested, and allowed to remain at peace. She was destined to be

the helpless prey of the first invader, and, though Britain would be

obliged to exert herself in defence of Portugal, when attacked, her

utmost exertions, though expensive and injurious to herself, would be

wholly ineffectual with regard to their proper end. Naples was near-

ly in the same situation, and the states anciently so formidable or re-

spectable, Sardinia, Holland, Switzerland, Venice, Rome, Tuscany,

Genoa, and Spain, were either wholly extinguished, or joined in in-

dissoluble bonds of alliance with the enemy.

The only powers of Europe that retained their independence, and

whose alliance or co-operation might be purchased without imminent

danger to themselves, were Turkey, Russia, and Prussia. Turkey

was little valued as a friend, or dreaded as an enemy. She was al-

most as impotent and helpless as Portugal or Naples, and even her

commerce was scarcely of as much value as that of those countries.

Russia, on the contrary, has been of late years treated with uncom-

mon deference and respect by all the states of Europe. Her alliance

has been courted with the utmost solicitude by all parties, and her in-

terference dreaded or desired as capable of deciding every controversy.

How she acquired this reverence is not easily discovered, since her

military power has hitherto been exerted, with any degree of success,

only against the Turks, who, in the arts of war, have relapsed into

barbarism, and against the Poles, whose political disunion and inferior

numbers sufficiently account for the success of their enemies. The

eyes of mankind have been dazzled by the great local extent and ra-

pid advances in culture and population of the Russian empire; by the

absolute authority of the prince; by the formidable amount of its

troops, as they appear in official statements and deplomatic reports;

and by its assiduous imitation of German tactics. It has not been

sufficiently considered that the empire of the Russians is, for the most

part, merely nominal, and comprehends little more than tribes whose

poverty and barbarism render their obedience equally useless and pre-

carious, or deserts rendered uninhabitable by sterility or cold; that

their advances are only remarkable when compared with their humble

and recent beginnings; and that if their gross population were equal

to that of France or Austria, yet their national strength must be less

when exerted in attacking others, exactly in proportion as their num-

bers are scattered over a wider surface. The genius of the Russian

government and manners is undoubtedly more akin, from whatever

cause it arises, to those of western Europe, than that of the Turkish

or mahometan system. The Turks occupy a country possessed of a

better climate and soil, and greater proportional population, than Rus-

sia. Their local relations with the west of Europe is more close and

intimate, yet the institutions, and arts, and political maxims of France

―12― ―12―

and Germany, have made much less progress among the Turks than

among the Russians. Religious peculiarities will not satisfactorily ex-

plain this difference, and the problem must remain unsolved, unless

we allow some influence to the personal character of Peter I, aided

by those connections of blood or marriage with the German princes,

which distinguished his successors.

It is not easy, at first sight, to perceive what occasions for enmity

or rivalship could arise between Russia on one side, and France and

England on the other. The former has no colonies or provinces be-

yond the main, nor any foreign trade of importance. This source of

contention, therefore, does not exist. The wide interval which se-

parates them renders the wars and conquests of Russia on her

neighbours of no such immediate consequence to France or England

as to justify their interference. In like manner, Russia has no ob-

vious concern in the contentions which might take place on the Po or

the Rhine, or in the English channel. Still, however, France and

England were prone to interfere, either from a meddling and domineer-

ing spirit, or from the apprehension of remote consequences in Rus-

sian affairs, and Russia has been led by personal vanity, by resent-

ment for airy insults, or by large subsidies, to take part in wars, the

proper theatre of which lay five hundred or a thousand miles beyond

her own border.* Thus France at one time, and England at another,

has, directly or indirectly, checked the progress of the Russians in

Turkey. If they did not interfere in the partition of Poland, it was

probably from the pressure of more immediate interests, or from the

impossibility of intermeddling with due weight against the threefold

combination of Russia, Austria, and Prussia. For more than half a

century, the Turkish provinces have been the great object of Russian

ambition. France has studiously raised obstacles in the way of her

wishes at one time, because the consent of Austria was to be previous-

ly obtained to this conquest, and Prussia could only obtain this con-

sent, by allowing Austria to participate in the spoil. Hence, as

France and Austria were, in some sense, contiguous and consequent-

ly rival states, it was incumbent on France to preserve Turkey, be-

cause Austria would be the stronger for her destruction. The same

motive, arising from a similar relation both to Austria and Prussia,

actuated Prussia to unite with France, for the protection of Turkey. At

a subsequent period, when Russia, Austria, and France coallesced to

divide the Turkish empire between them, the English, whose inter-

est lay in preventing any accession to the French power, interfered for

the preservation of Turkey, and thereby drew down upon itself the

enmity of the Russian sovereign.

When the French revolution broke out, the abhorence and alarm

naturally excited in all crowned heads, by the destruction of monarchy

* A curious example of the influence of wealth over poverty, and of the

power of the British nation over the affairs of the continent, occurs in a

treaty which the English made with the empress Elizabeth, in which the

former hires from the latter fifty thousand men, to march into Germany for

the safety of Hanover.

―13― ―13―

and the royal family in France, strongly infected the head of the Rus-

sian, and even of the Turkish empire. This, added to the attack of

the French on Egypt, cemented a strange and momentary alliance

between Turkey and Russia, and strengthened the amity between

Turkey and Great Britain. When the French were dispossessed of

Egypt, and disabled by the English from assailing any part of the

Turkish territories, they had only to renew their amicable intercourse

with Turkey, and regain an influence in its councils, by awakening

its ancient animosity to Russia, and to instil suspicions of England on

account of the alliance between Russia and that power. The rapid

triumphs of the French in Germany and Italy naturally augmented

the interest which the English had in the friendship of Russia, but

this friendship was to be bought only by withdrawing its protection

from Turkey in case of a future war between the Turks and Russians,

and this concession was the more readily made, because the aggran-

dizement of France had put a weight in one scale, which could only

be outweighed by some enormous addition to the other.

Such is partly the clue to that complicated labyrinth displayed by

the wars and negociations of the states of Europe, for the last twenty

years. Such were the circumstances that led to the alliance between

England and Russia, which subsisted in the year 1806, and to that

state of hostility subsisting, at the same period, between Russia and

France. The proper theatre of these hostilities were, indeed, shut

up from the parties, by the peace that reigned in Germany and Tur-

key. The Russians could appear upon the Danube, the Elbe, and the

Rhine only as the ally of Austria or Prussia; but these powers were

at peace with France. France could not, and had no interest to induce

her to send an army into Poland, and the peace of Turkey allowed her

not to encounter Russia on that stage as a confederate of the sultan.

A petty contention was, however, kept up in a remote corner of Dal-

matia.

In pursuance of the last treaty between Austria and France, the

former ceded to the latter all those provinces which anciently belong-

ed to Venice, and which, at the conclusion of a former war, were as-

signed to Austria, as the price of the surrender of the Netherlands to

France. The Venitian dominions extended along the eastern shore

of the Adriatic, about three hundred miles from the head of that sea.

At the point where the Venitian territory ended, a small district be-

gan, belonging to the small republic of Raguza. Raguza enjoyed in

some sort a political independence of all its neighbours. A moderate

tribute or present was payable, however, to the Turkish sultan, every

three years, which secured them not only from all internal interference

by that power, but its protection from all other powers, and considera-

ble commercial privileges in the ports of the Turkish empire. This

happy little state enjoyed a long period of tranquility, till the Russians

and the French made its territory the scene of their bloody conten-

tions.

The Raguzan territory terminates, on the south, at a river or inlet

of the sea, called the Cattaro, the mouths of which were capable of

being made strong military stations, and were included in the latest

―14― ―14―

cession to the French. The seven Grecian islands formerly belong-

ing to Venice, and erected by the French into a nominal republic,

were, in the year 1806, in possession of the Russians. Corfu, one of

these islands, is adjacent to the Dalmatian coast, about two hundred

miles below the Cattaro, whose mouths, together with the neighbour-

ing districts, were therefore occupied by their forces. The wild and

independent tribes in the neighbouring hills, united with the Russians

in carrying on a desultory and destructive war against the French,

and no efforts on the part of the latter had hitherto proved entirely

successful. In every other quarter, the two nations were prevented,

by long intermediate tracts of land or sea, from coming to blows.

Prussia was the third state in Europe, whose internal strength and

political independence made its alliance desirable, or its enmity formi-

dable, to Great Britain, but Prussia had been for some years united in

the closest apparent amity with France. The deep rooted jealousy,

and irreconcileable interests of Prussia and Austria had yielded, for

a moment, in the early days of the French revolution, to the common

terror of republican France. This alliance was speedily dissolved,

and the obvious policy of purchasing the connivance and forbearance

of Prussia, by enriching it with the spoils of England and Austria,

has been practised by the French with the greatest success. The

general principle, by which all states are governed, of aggrandizing

themselves, actuated Prussia in maintaining a strict neutrality in the

wars of France against England, Austria, and Russia, and this conduct

was far more gainful than war. The French were deeply interested

in keeping Prussia quiet, and rewarded her, at the close of every war,

with valuable territories chiefly ravished from the petty princes of

Germany. Had it been possible to foresee the total discomfiture of

Austria, in the war of 1805, the Prussians would probably have per-

ceived, that war with France, at that critical juncture, was dictated by

the wisest policy. That conjuncture of affairs, however, was so brief, and

the event so little within the reach of human foresight, that the inactivity

of Prussia, impartially considered, detracts nothing from her reputation

for political wisdom. Her neutrality was amply recompenced by the

annexation of Hanover to her empire, a gift in the highest degree

judicious, not only on account of its intrinsic value to the receiver, but

because, being originally the property of the king of England, and ra-

vished from him by force of arms, the breach would thereby be widen-

ed between the old and the new possessor. This consequence accord-

ingly ensued, and several indications appeared, about this time, that

menaced an actual war between England and Prussia.

―15― ―15―

CHAP. III.

IN this state of things, when England was obliged to resign all

hope of effectual co-operation from the continental powers; when all

that was vulnerable or accessible in the empire of France, had been

previously acquired; and when France had exhausted all the means

in her power of distressing her rival, the continuance of war between

them caused to be subservient to the glory, revenge, or benefit of ei-

ther party. War prevented France from restoring her commerce and

industry, and subjected England to an enormous and destructive ex-

pence. The advantages of peace, therefore, became every day more

evident to both parties; and a change in the English ministry, oc-

casioned by the death of Mr. Pitt, seemed to bring that desirable

event within reach.

The war against France commenced under the auspices, and in

persuance of the councils, of the deceased minister. Mr. Fox, his

great political rival, had made incessant and uniform parliamentary

opposition to this war, and condemned not only the grounds and pre-

texts on which it had commenced, but almost every step in its pro-

gress. He was, at all times, the vehement advocate of peace, and the

period had at last arrived, when the death of Mr. Pitt, and the equili-

brium between France and England, gave admission to Fox and his

pacific principles into the councils of the British government.

A private letter from Mr. Fox to Talleyrand, the French minister

for foreign affairs, relative to a project suggested to the former for

assassinating the French emperor, opened the way for a correspon-

dence between them, which commenced in February, 1806. In these

letters a mutual desire for peace is expressed, and each one recognizes

the claim of the other to terms of absolute equality. As the friend-

ship of Russia was highly valued by the English, great pains were ta-

ken by Mr. Fox to convince the French, that though each might treat

separately, nothing could be finally done without the full concurrence

of Russia. The French were not blind to the obvious policy of disuniting

these allies, and that dexterity and artifice, in which the French excel

all other nations, were exerted for the purpose, but entirely without suc-

cess, with regard to England. About the middle of June, lord Yar-

mouth, at that time a prisoner in France, became the medium of in-

tercourse between the two ministers, and in August, the earls of Lau-

derdale and Yarmouth held formal conferences with Champagny and

Clarke, at Paris, as plenipotentiaries, on this important subject. In

the early part of this negociation, some incautious expressions of

Talleyrand, admitted as equitable the claims of the British, first to

retain all their conquests, and, secondly, to have Hanover restored to

them. Sicily, being at this time in possession of the British, was in-

cluded in the required cession, but the importance of this island to

―16― ―16―

France occasioned an extreme and equal solicitude in both parties to

retain it. Some districts on the eastern coasts of the Adriatic, at one

time, and the Balearic islands at another, were offered as a recom-

pence for Sicily, but the superior value of the latter island, not

only in itself, but as in some degree necessary to the preservation of

Malta, the greater part of whose subsistence is derived from Sicily,

with the facility of defending it by a naval power, were insuperable,

obstacles to any such exchange. In exchange for these advantages,

the English merely offered to acknowledge the actual governments

of France, Holland, and Italy, and leave the French in possession of

all their acquisitions; provided, necessarily, that Russia fully con-

curred in this agreement. It is amusing to see, in the various parti-

culars of this conference, the vigilance and ingenuity exerted by both

parties, to obtain some advantage over the other. The English are

diligent in maintaining, as the only ground of a treaty, the retention of

all their own conquests, and the restitution of Hanover, and in re-

minding the French agents, that these claims had been originally ad-

mitted by their minister, while the French, on the other hand, by si-

lence or evasion, escape from the consequences of their first conces-

sion, and, by fluctuating between concession and refusal, prolonged the

conferences to the sixth day of October, when, eight months after its

commencement, the negociation terminated in the absolute refusal of

the French, to allow their adversaries to retain Sicily, or to restore

Hanover.

The former of these points appears to have been the great difficulty,

on both sides; yet its value to the English was merely indirect, since

they aimed not to hold it themselves, but merely to secure it to its own

prince. The transfer to France would considerably augment the

power of their enemy, though its independence would be of little direct

benefit to themselves. It is not easy to imagine how the British go-

vernment purposed to secure the independence of Sicily against the

future attempts of France. It could only be done by maintaining at

Malta a considerable naval force, sufficient to frustrate any sudden at-

tempts at invasion, or by garrisoning the island with an English army,

supported at their own expence, or at that of the Sicilians; but either

of these arrangements would be productive of great inconvenience.

Though the French agents could not succeed in persuading the

English minister to treat with them independently of Russia, they

were less unfortunate in their efforts to detach Russia from England.

P. D'Oubril, an agent dispatched to Paris for making arrangements

respecting the exchange and maintenance of Russian prisoners, was

persuaded to sign a treaty on the 20th July, 1806, in which the empe-

ror of Russia consented to abstain from any further interference in

the affairs of western Europe. He was made to promise to give up to

France the mouths of the Cattaro, and all other stations in Dalmatia

possessed by his troops, while Napoleon promised on his part that,

within three months after giving the order for the surrender of Cat-

taro, all the French troops should leave Germany. As the terms of

this treaty were directly opposite to the avowed intentions of the Rus-

―17― ―17―

sian government, and the alliance between Russia and England, the

French could not flatter themselves that it would be ratified at Peters-

burg; but it was obtained from the Russian agent by a series of labori-

ous artifices, merely to impress the English with an apprehension of

being deserted by Russia, and thus either to induce them to make a

separate treaty, or to relax in their demands.

If we take an impartial view of this negociation, we shall be obliged

to acknowledge that the conduct of the English throughout was can-

did and upright, while that of the French was full of subterfuge and

sophistry, equally disingenuous and fruitless. They were evidently

much deceived in their notions of the views and temper of the new

British ministry. Mr. Fox had expended so much eloquence in con-

demning the principles and conduct of the war, that France naturally

concluded that he would hasten to terminate hostilities by any sacrifice,

when power should come into his hands. On the contrary, the de-

mands of the English were such as certainly implied, that the meed of

success, in the long protracted warfare, had been allotted to them.

They not only insisted on retaining all they had conquered, but re-

quired the restitution of a province, which it was impossible to wrest

from France by force of arms, and which France had given already to

an ally, who would never have peaceably surrendered it. With re-

gard to Hanover, however, there is reason to think, that England

would not have made its restitution an indispensible condition of peace.

In the hands of Prussia it could do the English no harm. If re-

stored, it would not become the property of the nation, but merely an

expensive and burthensome appendage, which, unprofitable as it was,

could not be defended in a new war. The pleas of the British, that

Hanover ought to be restored, because it was unjustly attacked, were

plainly nugatory and absurd. The distinction between England and

Hanover, between the nation and the king, was sufficiently intelligible

to an English lawyer, but was a ridiculous refinement in the eyes of

foreigners. Its folly was indeed evinced by the stress laid, by the

English government, on its restitution.

If the English acted in this negociation as conqueors, and as if the

peace that was to follow was granted as a favour to France, the

French, on the other hand, in demanding certain islands in America,

taken from the Dutch, and the cession of Sicily, without any reasonable

compensation, assumed in like manner the tone of conquerors. The

events of the war, immediately relative to England, certainly did not

justify this haughtiness in France, but neither did the issue of the

contest between France and the allies of Britain justify a lofty tone in

England. Both nations had advanced greatly in power since the com-

mencement of the war, but undoubtedly France had made the greater

progress; yet, in the power of annoying England, the naval successes

of that state had certainly reduced her rival to a lower point than she

occupied before the revolution. No war waged by Great Britain for

many centuries has been crowned by more splendid and uniform suc-

cess than the present. As an insular and commercial state, all her

efforts for her own protection, and for the extension of her proper em-

―18― ―18―

pire, have been victorious in the amplest manner. Her colonies and

distant provinces were safer from molestation than ever, and, so far as

the facilities of invasion depend upon naval power, her security was

greater than it had ever been before. The numbers, unanimity, and

zeal of the people, the vigour of the government, and its military pre-

paration, was certainly much greater than at any period of the eigh-

teenth century; and if France could muster greater armies than for-

merly, this advantage, however, real, was probably outweighed by the

depression of her naval power, if not by those favourable circum-

stances, already mentioned, in the internal state of Great Britain.

There was one point of view, however, in which the difference was

apparently very disadvantageous to Great Britain. The national re-

venue of France was the fruit of great and oppressive taxation, but it

was sufficient to defray the annual expences, and does not appear to

have encroached upon the capital fund, or to have impaired the

sources of future revenue. The stock on which the public made its

levies was not likely to grow less from year to year, nor taxation to

grow more oppressive, or less certain and productive. The situation

of England was directly opposite: of the public revenue, the proportion

set aside for other purposes than that of supporting fleets and armies

was annually augmented, and hence, though the defence of the nation

should cost no more at one time than another, yet the burthen of tax-

ation continually increased, and a general apprehension prevailed that

the nation was not far from that point, when any further addition to the

taxes would be impossible. As this state of things will oblige the

government to suspend the payment of the interest of the public debt,

and thus deprive an incredible number of persons of their usual means

of subsistence, such an event is commonly, though erroneously, re-

garded as equivalent to utter ruin*. A peace, by lessening the current

expences of the state, diminishes taxation; or, at least, prevents its an-

nual increase. Hence it is immediately conducive to the well-being

of the people, while, at the same time, it puts the dreaded catastrophe

further off. Such, however, is the national spirit of the English, that

the pressure of immediate, or the apprehension of future evils, how-

ever they may be occasionally magnified by the rhetorick of inexpe-

rience or of faction, has never lessened their regard for what is called

national honour, or tempted them to make any sacrifice, which im-

plied military superiority in an enemy. Either that taxation, so much

* It is somewhat adventurous to speculate upon the consequences of a na-

tional bankruptcy in England. An event, whose influence must necessarily

be so extensive and complicated, can hardly be subjected to calculation; yet if

all extravagance and rhetorical exaggeration be laid aside, every one must al-

low, that, whatever proportion of the nation suffers by it, and whatever be the

extent of this suffering, the injury must, of necessity, be temporary, while the

benefit is vast and permanent. In its immediate effects, it cannot render the

state less formidable to other states, and, in its ultimate effects, it must, in a

wonderful degree, augment its power. Public bankrupt is not without nu-

merous examples. France itself owes much of its actual force to this very

circumstance.

―19― ―19―

talked of, is more a nominal than real burthen, either the fund that

supplies it increases in the same proportion with itself, or there is

something in the modes of expenditure which counteracts the primary

evil; for the taxes of late years are paid with as much facility, and with

as little reluctance, as in former times, and the government actually

succeeds in raising all that its occasions demand, and much more than

the theoretical observers of former times conceived to be possible.

A general view of the trade and revenue of the British empire leads

to astonishing conclusions. The annual charge, which includes the

expence of management, on account of the British public debt, in

the year 1806, amounted to more than twenty-seven millions and

three quarters sterling. This charge had increased, during the fore-

going four years, about four millions and a quarter. The sum neces-

sary for the support of civil government, and for the general defence,

amounted to nearly fifty-five millions and a half. Of this sum, two

millions and a quarter were absorded by the mere expences of collect-

ing and managing the whole. The annual charge on the national

debt added to this sum, appropriated to the other current expences,

raise the whole to eighty-three millions and a quarter pounds sterling.

Of this gross amount, very near thirty-two millions was paid by

wealthy individuals, in the form of loans, bearing interest. Upwards

of five millions was levied in Ireland, and the remainder, or about forty-

three millions and three quarters, in Great Britain, in the form of

taxes. The annual parochial assessment, in Great Britain only, for

maintenance of the poor, amounted to upwards of five millions. By

this detail it appears, that the national debt did not aggravate the actual

burthen of taxation, since the loans of this year not only defrayed the

interest and charges accruing on the previous debt, and even accruing

on themselves, but contributed near five millions towards defraying

the current expences of civil government, and the general defence.

It is this facility of borrowing to so enormous an amount that consti-

tutes the most striking feature in the political economy of this nation.

The public debt ceases to be an actual burthen, as long as the whole

interest and charges are defrayed by new voluntary loans. However

enormous it may be, it cannot be considered as shackling or encum-

bering the operations of the state, till that period when the annual

charge created by it is defrayed, in some proportion, by taxation. Its

constant augmentation affords the melancholy certainty, that such a

period must arrive; but this is no present evil*.

The average annual value† of imports into Great Britain, during the

last nine years, amounted to sum between twenty-nine and thirty-

one millions. The last six years of this period had produced a larger

average than the three preceeding; but the imports of 1805 were less

in value, by two millions, than those of 1802. The real value of

* On the stock created in 1806, the interest and all charges amounted to

a proportion of nearly three and one-sixth per cent.

† In this statement, the official value is meant, which is always much below

the real value. It serves at least as a medium of comparison. The official to

the real value is commonly estimated in the proportion of about five to eight.

―20― ―20―

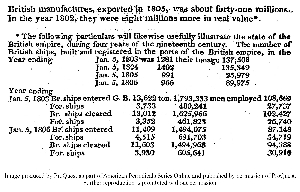

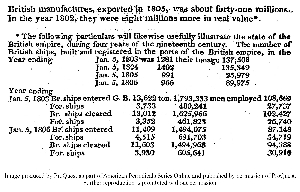

British manufactures, exported in 1805, was about forty-one millions.

In the year 1802, they were eight millions more in real value*.

* The following particulars will likewise usefully illustrate the state of the

British empire, during four years of the nineteenth century. The number of

British ships, built and registered in the ports of the British empire, in the

| Year ending |

Jan. 5, 1803 |

was |

1281 |

their tonage |

137,508 |

|

Jan. 5, 1804 |

|

1402 |

|

135,349 |

|

Jan. 5, 1805 |

|

991 |

|

25,979 |

|

Jan. 5, 1806 |

|

966 |

|

89,975 |

| Year ending |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Jan. 5, 1803 |

Br. ships entered G.B. |

13,622 |

ton. |

1,793,333 |

men employed |

108,669 |

|

For. ships |

3,733 |

|

480,241 |

|

27,737 |

|

Br. ships cleared |

13,012 |

|

1,625,966 |

|

102,427 |

|

For. ships |

3,352 |

|

461,823 |

|

26,740 |

| Jan. 5, 1806 |

Br. ships entered |

11,409 |

|

1,494,075 |

|

87,148 |

|

For. ships |

4,515 |

|

691,703 |

|

34,719 |

|

Br. ships cleared |

11,603 |

|

1,494,968 |

|

94,388 |

|

For. ships |

3,930 |

|

605,641 |

|

30,910 |

―21― ―21―

CHAP. IV.

WE have already mentioned, that the war between France and

England was almost entirely confined to the operations at Boulogne,

operations which consisted, on one side, chiefly in watching an oppor-

tunity to leave that harbour, and, on the other, to prevent the enemy

from leaving it. Nothing but the superiority of a great naval force

prevented the French from landing in Great Britain; but to maintain

this superiority, and imprison the French in their own harbours, ap-

pears to be the sole purpose of the English, in relation to the French

territory. For more than two centuries, all projects of regular and

permanent conquests in France have been relinquished by the English.

Expeditions have been occasionally made, and troops been landed, on

the French coast, but merely to assist a party at a period of civil war,

as the hugonots in former times, and the royalists of late years, or to

destroy shipping and maritime fortresses. This system of conduct

has arisen from a rooted persuasion, that no permanent impression

could be made against the military and internal force of France, acting

upon its own ground. This opinion cannot be better grounded in re-

lation to France than to Great Britain; and France seems to have seri-

ously meditated no design of invading England, since the claims of the

Stuart family have become extinct, or obsolete, and all hope of a co-

operating insurrection was by this means removed, til the ascendency

of Buonaparte was established in France. The turbulent state of Ire-

land has indeed afforded, since the opening of the French revolution,

a strong temptation to the enemies of England, and, for some time, all

the French projects of invasion was confined to that island. Buo-

naparte, more fortunate and daring than any of his predecessors, con-

ceived the hope of effecting a total conquest of England itself, and un-

doubtedly awaits with impatience an opportunity for making the at-

tempt. The English, instead of assailing any part of the French ter-

ritory, have hitherto contented themselves with checking and opposing

the French in their distant expeditions, where a powerful navy was at

hand to recruit her own forces, and cut off all supplies from the enemy,

and where her efforts were in some degree seconded by the government

and natives of the country which formed the scene of warfare. In

this way, the utmost diligence was used to intercept the French arma-

ment destined against Malta and Egypt. When these places were

subdued by the French, they were attacked by the British; but, when

the French were dispossessed of these, there was no part of their con-

quests accessible but Sicily and Naples.

The kingdom of Naples has for ages been the sport and prey of fo-

reign conquerors. The French, Spaniards, and Austrians, have alter-

nately been masters of this opulent and fertile country, and, in an ab-

stract view, the government of all these nations has been mere usur-

pation. Some of them, however, have remained masters so long, that

their claim have acquired the sanction of custom and prescription, the

―22― ―22―

only basis on which political authority can safely rest. When the

French first invaded Italy, their political opinions had previously

smoothed their path, and Rome and Naples were metamorphosed into

republics. When the Austrians were finally expelled from Italy

by Buonaparte, and the republican system in France entirely exploded,

the kingdom of Naples was revived, and bestowed upon a brother of

the French emperor, as a feudal or dependent principality. The

French, however, had never perfected their conquest of the Italian

provinces of the kingdom. The southern districts, called the two

Calabrias, are very mountainous. They are inhabited by an ignorant,

hardy, turbulent and ferocious race of men, whom their attachment to

their former sovereigns, or the military violence and licence of the

French, have inspired with a deadly aversion to their new masters.

The nature of their country, abounding in sharp hills and narrow val-

lies, raised peculiar difficulties in the way of an enemy; and as the

English are masters of the sea, the efforts of the natives were conve-

niently aided by occasional detachments of troops, and by supplies of

arms and ammunition. The narrow channel which divides Italy from

Sicily enabled the English to preserve that island entirely free from

the French yoke, and from this station to watch and improve every

opportunity that offered of alarming or disturbing the opposite shores.

The English force in this quarter was never sufficient to authorize

an attempt to drive the French from the southern provinces of Italy.

Four or five thousand men appear to be the utmost amount of the

forces which they could conveniently employ on one expedition.

The French had twenty or thirty thousand men at hand, and could

conveniently augment that number by auxiliary detachments from

upper Italy. This scene of contention, therefore, was distinguished

chiefly by a series of petty skirmishes between the French and the

shepherds of Calabria, in the vallies and defiles of that province. Nor

does the course of 1806 afford any other memorable occurence

than a useless battle between the French and English at Maida.

About the beginning of July, the English and Sicilians appear to have

meditated the expulsion of the French from the province of further

Calabria. This district forms the extremity of Italy on the south.

It is a rugged peninsula, severed at the lower end by the strait of

Messina, from Sicily. The French occupied many fortified posts in

this province, but their greatest force was collected at Reggio, the chief

town, situated at the southern end, on the strait of Messina, a post fa-

vourable either for making any attack on Sicily, or repelling any from

the same quarter. While the French commander, Regnier, was oc-

cupied at this post in watching the opposite shores, the English, under

general Stewart, landed near five thousand men, at the gulf of St.

Euphemia, in the northern border of the province, and about fifty miles

from Reggio. The French general, on receiving tidings of the event,

lost no time in marching against them. He hastened northward, at

the head of four thousand foot, and three hundred cavalry, leaving di-

rections for an additional force of about three thousand to follow him.

On the third of July he had advanced within ten miles of the English,

who still continued at the place of disembarkation. The news of

―23― ―23―

Regnier's approach induced them to move forward, and the two ar-

mies accordingly came next day in sight of each other. The English

were desirous of meeting the enemy before their army was reinforced

by the division which Regnier had ordered to follow; but this junction

was effected on the third, though the English were not apprized of

this circumstance till after the battle. The French chose a very ad-

vantageous station for their camp. They posted themselves on the

side of a woody hill, with a village behind them, and an impenetrable

thicket on either side. The hill sloped into the plain of St. Euphemia,

over which the English army was obliged to pass. A river, every

where fordable, ran in front of the French encampment; but the sides

of this stream were soft and marshy. Had it been the design of the

French to wait an attack, they could not be more advantageously

posted, while the situation of the English, in an open plain, with an

inferior force, and unprovided with cavalry, was extremely hazardous.

In these circumstances, the most prudent course that could be taken

by the French was quietly to keep this station till the English were

compelled, either to a desperate attempt on their entrenchments, or to

make an inglorious and dangerous retreat. The usual impetuosity of

Regnier, with the manifest advantage of cavalry, and of superior num-

bers, rendered the scheme of attacking the English on the plain not

the safest, but, at the same time, an highly eligible one. Regnier ac-

cordingly left his inaccessible post, and marched down into the plain to

meet his adversary. The field was sufficiently remote from the sea

to prevent the co-operation of the English shipping, under Sir Sidney

Smith; but that commander had placed his force in a manner most

favourable for protecting the retreat of his countrymen.

According to the English statements, and these only have been pub-

lished, the adverse forces amounted, on the English side, to four thou-

sand eight hundred men, with sixteen pieces of cannon, and, on that of

the French, to at least seven thousand men, with cavalry and artillery

in a proportion not particularly ascertained or mentioned. The battle

appears to have lasted but a short time, and to have ended in the total

rout and dispersion of the French. The contest on one wing seems

to have been decided by one of these inexplicable movements of feel-

ing, which can enter into no military calculation. The opposing

bands, on the right of the English line, after exchanging a few rounds,

silently advanced against each other till other bayonets crossed, when

the French suddenly broke their order and fled. On the left, the con-

flict was more obstinate and regular, and seems to have been princi-

pally decided by the sudden arrival of an English regiment, who landed

the same morning from Messina, and who reached the field just as the

French cavalry, after being repulsed from before the British front, were

attempting to turn their left. The new comers, observing this move-

ment, threw themselves into a small cover, and, by their fire, checked

and disconcerted the enemy. After this there was a precipitate and

confused retreat, accompanied with great slaughter of the French.

The slain, wounded, and prisoners amounted to upwards of four thou-

sand on the side of the vanquished; while the British lost forty-five

killed, and two hundred and eighty-two wounded. Though the vic-

―24― ―24―

tory contributed to raise the reputation of the British arms, it does not

seem to have contributed any thing to the conquest of the country.

The French easily drew large reinforcements from the other pro-

vinces, and the English army re-embarked shortly after, and returned

to Sicily. The rest of the year passed away without any military

operations of any consequence in the Mediterranean. The French,

shortly after this, had their hands fully occupied in Germany and

Poland, and could not spare troops for the invasion of Sicily, while the

destruction of their fleet in the preceeding year at Trafalgar disabled

them from making any efforts at sea. They were contented to de-

fend their own coasts and harbours, while the English, after this diver-

sion in Calabria, were satisfied with the quiet possession of Sicily and

Malta.

The naval power and commercial habits of the English naturally

led them to attack the colonies and remote possessions of their ene-

mies. During the present war, they have taken from the Dutch

many valuable possessions in the east, and the Africa. After the peace

of Amiens, they restored the Cape of Good Hope, but on the renewal

of the war it was speedily re-conquered, and is now probably become

a permanent acquisition. The island of Java, and the isles of France

and Mauricius, with some settlements in Madagascar, were all that

remained to France and her allies in the African and Asiatic seas.

Java, on account of its intrinsic opulence, and the isle of France, from

the convenience of its position to annoy the English commerce in the

east, would naturally provoke a hostile attack. The latter is ren-

dered nearly impregnable by peculiarities of situation, and the former,

from the pressure of more immediate and important concerns, has

been hitherto allowed to remain in the hands of the Dutch.

It is somewhat surprising, at first sight, that the dominions of Spain

in South America have never been formally attacked by the English.

They contain the richest mines of the precious metals known in the

world. They abound with every vegetable product, to which the lux-

uries or necessities of European nations annex any value. They are

commonly supposed to be very weakly defended, either by fortresses

or soldiers. The people are thought to be discontented with their

government, and ripe for any revolution; to be the prey of domestic

faction; and disabled, by effeminacy, indolence, and a long inexperience

of war, for any effectual resistance. Hence, in a war between Eng-

land and Spain, these provinces would naturally present themselves as an

easy and desirable prey to the former; yet no regular attempt was

ever made to obtain a footing in South America, till the year 1806.

Cuba and Trinidad have, indeed, at different times, been conquered;

and Carthagena and Portobello, on the coast of Mexico, have been in-

effectually attacked in former wars; but the splendid regions of La

Plata, Chili, and Peru were unmolested.

After the revolution in North America, an opinion began to gain

ground in England, that colonial establishments were on the whole

injurious; that they diverted the enterprise, industry, and capital of a

nation from the cultivation and improvement of its own soil to more

specious but delusive projects, connected with remote regions, from

―25― ―25―

which no real or permanent advantage redounded to the parent state,

equivalent to the wars, luxury, and enormous public expences which

they necessarily occasion. The mind was naturally led to this con-

clusion, by reflecting on the expensive wars undertaken by England,

for preserving, from the encroachments of France, these provinces of

North America, which, in less than twenty years after their rescue was

accomplished, revolted from the parent country, and involved it in a

new war, far more expensive than the former, and from observing

that Spain has become feeble and powerless since her empire was es-

tablished in the New World. The imagination naturally supposes

the colonies of Spain to be the cause of her decay, and as the same

effect did not follow from the colonial system of France or Great Bri-

tain, we immediately suspect that this difference arises from some dif-

ference in the colonial systems of the several states. As vast quanti-

ties of silver are manufactured and exported in the Spanish colonies,

and none in those of other countries, we immediately fancy that the

true cause of the decay of Spain is discovered, and that an extensive

manufacture, or rather importation of the precious metals is the bane

of industry, liberty, and science, and military virtue. These opinions

have had a powerful influence on the conduct of states, and made the

Spanish dominions, rich, fertile, and extensive as they are, objects

of abhorence, rather than of envy to their neighbours. These opinions

contributed to their security from all external attacks.

As South America is found, on more accurate enquiry, to have real-

ly advanced in population since the first settlement, and to have a con-

siderable demand for the manufactures of Europe, the British govern-

ment, which imagines that the national prosperity cannot be more es-

sentially promoted than by opening a new channel for trade, and find-

ing out a new market for their manufactures, especially in times

when they run some hazard of being excluded from the markets of

Europe, have begun of late years to imagine that the Spanish colonies

were worth obtaining, not for the sake of their mines or taxes, but

merely of the custom which their numerous and luxurious inhabi-

tants would afford to their own work-shops. The difficulty and ex-

pence of maintaining their authority over a people, so hostile in reli-

gion and manners, have not been thought of much importance. Per-

haps indeed by robbing Spain of what, whether deservedly or not,

she considers of great value, the chief advantage proposed by the Bri-

tish government was to have some pledges in its hands for an equita-

ble peace.

Notwithstanding these general reflections and opinions, it does not

appear that the British ministry had finally resolved to attack any of

the Spanish settlements in South America. The attack upon Buenos

Ayres was made without the knowledge or orders of the government,

and by a fleet and army which they had destined to a different service.

The armament under admiral sir Home Popham and general Baird,

dispatched, in 1805, against the Cape of Good Hope, having soon

effected the conquest of that colony, these officers remained for sever-

al months inactive on that station. Orders were dispatched to them

in September, 1805, to proceed with the fleet and part of the army to

―26― ―26―

India; but these orders miscarried, and they were left till the month

of April, in the ensuing year, without any particular directions for their

future conduct. In this interval the admiral received a letter from

an American captain at the cape, which painted in very strong co-

lours the defenceless situation of the Spanish settlements on the River

La Plata. The chief of these settlements, Buenos Ayres and Monte

Video, he described as abounding with all kinds of provisions, as in-

habited by a discontented and timid people, whom a few cannon-shot

would frighten into a surrender, and whom the benefits of a free trade

would speedily convert into voluntary and zealous adherents of a new

government. This representation, added to some vague reports of

the great wealth of these provinces, induced sir Home Popham to un-

dertake the expedition with the whole naval force at the Cape. Gene-